Chinese Riddle 3: Deconstructing Sinogrammes

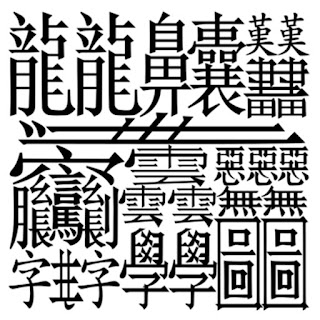

I cannot but smile when I hear futile discusions about the application of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis to Chinese. If language shapes your way of thinking, what do you have in your head when you write this character - Leviathan?

I haven't still entered that marvellous world of the word-sentence, that ancestral art of Arabian, Japanese and Chinese civilizations where a sentence is beautifully disposed as a word, conveying a deep philosophical meaning. This looks like to summit of the high and steep mountain of chinese characters, aka sinogramms, but if we start from the very base, we can make our first steps in character composition by looking at sign posts like this ones in some restaurants in Hong Kong:

Examples like this one raise some questions: Is this a bilingual inscription? What does the second character represents? What is its meaning and its subparts? What is this pictographic game about?

Well, as every character occupies roughly the same space in an imaginary square, we can distinguish two characters: one simple at the left, meaning "fight", and a character in the right that means "fresh", and is composed by two characters. The title in Chinese is therefore different from the English one; it is "Fight for freshness", and the character for "freshness" contains a kind of logographic pun: it is composed by 鱼 'yu' (or 魚 in the traditional version), "fish", and by 羊 'yan', "lamb". The logographic pun is easy: In its fight for freshness, fish changes its shape and becomes sushi.

But why does the combination of fish and lamb mean "fresh"? Maybe because these are the foods that you really need to eat fresh? Maybe there is any other reason, or maybe there is no reason. In any case, it seems that what is important is not the real origin, but the answer that each speaker gives to himself, because this answer will create a mental image that will become a tool for remembering the meaning of the character. This means, of course, that Chinese characters may have a clear logographic meaning, or may not, but what is important in them is the motivation, the association that speakers do between the character and a given content, in order to facilitate its memorisation and classification.

So you can see: Chinese characters are signs, just are those described by Saussure, without natural relationship between form and meaning, but with a psycological link, called motivation.

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario