Grammar of (Fake) Formosan

In a word, how would you like to be know for eternity ?

You may think... a great linguist, a great lover, a good friend, a good father, mother, teacher, person, singer, cooker, explorer, architect, doctor...

You may strive hard to engrave your honorable word in the stone of eternity, but you will never get the unique label used to describe George Psalmanazar: impostor.

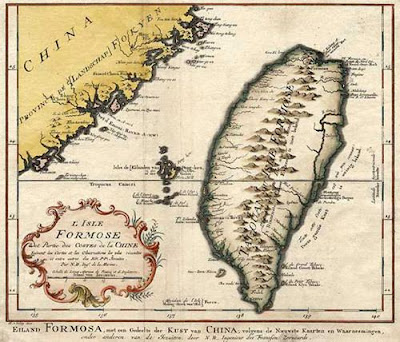

In the early 1700s, a French scholar managed to fool Europe's greatest intellectuals making them believe he was formosan (aka Taiwanese). So elaborate was his description of the exotic island's customs that he was even invited to give a conference in Oxford, creating a Formosan craze of Gangnam style propostions.

Even when he was unmasked, without changing his name, he reinvented himself as the hoax-creator in his 380 pages Memoirs. It would be more precise to say that this perfected hoax created him. First, as The Formosan, and later as The Fake Formosan. This gave him the fame and respect he was looking for.

Some books, some articles and many websites tell the fascinating story of the impostor Psalmanazar, who presented as true the description of a remote land not so different from Swift's descriptions in Gulliver Travels.

You can find some information about him here:

Among the many descriptions of the island's customs, there is one that I find fascinating: the invention of "Formosan" language. Psalmanazar's publication presents a description of the language, alphabet and English - Formosan linear translation of some prayers, as was customary in linguistic description.

Among the many descriptions of the island's customs, there is one that I find fascinating: the invention of "Formosan" language. Psalmanazar's publication presents a description of the language, alphabet and English - Formosan linear translation of some prayers, as was customary in linguistic description.

Interestingly, Psalmanazar will be remembered in the history of linguistics for adding two new lines to the list of reasons to invent a language: "To fool educated people and earn celebrity and respect". As the scholar he was, he knew Latin and Greek, and some Hebrew names from the Bible, and from this material he started to develop his conlang, or constructed language.

Psalmanazar "Formosan" displays a similar state of evolution as English or Romance languages today regarding syntactic marking: pronouns have case inflexion, while NPs mark their fonction with prepositions. Nouns are marked for number, and at last some of them, for gender, just like English (father vs. mother, etc)

We also find some suffixation, as the agentive - akhin

You may think... a great linguist, a great lover, a good friend, a good father, mother, teacher, person, singer, cooker, explorer, architect, doctor...

You may strive hard to engrave your honorable word in the stone of eternity, but you will never get the unique label used to describe George Psalmanazar: impostor.

In the early 1700s, a French scholar managed to fool Europe's greatest intellectuals making them believe he was formosan (aka Taiwanese). So elaborate was his description of the exotic island's customs that he was even invited to give a conference in Oxford, creating a Formosan craze of Gangnam style propostions.

Even when he was unmasked, without changing his name, he reinvented himself as the hoax-creator in his 380 pages Memoirs. It would be more precise to say that this perfected hoax created him. First, as The Formosan, and later as The Fake Formosan. This gave him the fame and respect he was looking for.

Some books, some articles and many websites tell the fascinating story of the impostor Psalmanazar, who presented as true the description of a remote land not so different from Swift's descriptions in Gulliver Travels.

You can find some information about him here:

- A 11' informal video

- A more complete 39' video

- His works and his memoirs in pdf, and html

- The Native of Formosa, from the website hoaxes.org

- George Psalmanazar, Fake Formosan

- “The Formosa Fraud: The Story of George Psalmanazar, One of the Greatest Charlatans in Literary History”

- The Fake 'Asian' Who Fooled 18th-Century London

- How A Blond, Blue-Eyed Frenchman Fooled Europe Into Thinking He Was Taiwanese

- Wikipedi'as article on George Psalmanazar,

- Swift's Psalmanazar: When 'Titillating' Means More Than 'True'

Among the many descriptions of the island's customs, there is one that I find fascinating: the invention of "Formosan" language. Psalmanazar's publication presents a description of the language, alphabet and English - Formosan linear translation of some prayers, as was customary in linguistic description.

Among the many descriptions of the island's customs, there is one that I find fascinating: the invention of "Formosan" language. Psalmanazar's publication presents a description of the language, alphabet and English - Formosan linear translation of some prayers, as was customary in linguistic description.Interestingly, Psalmanazar will be remembered in the history of linguistics for adding two new lines to the list of reasons to invent a language: "To fool educated people and earn celebrity and respect". As the scholar he was, he knew Latin and Greek, and some Hebrew names from the Bible, and from this material he started to develop his conlang, or constructed language.

Psalmanazar "Formosan" displays a similar state of evolution as English or Romance languages today regarding syntactic marking: pronouns have case inflexion, while NPs mark their fonction with prepositions. Nouns are marked for number, and at last some of them, for gender, just like English (father vs. mother, etc)

Nominal morphology

Among the gender differences in nouns, we find several iregularities, just like in English and French:

There is some degree of word-creation by compounding:

Regarding number, few nouns display a distinct morphology for plural. Th given examples have an -os ending:

Articles are used only in some occasions, specially plurar ones, which are rare. They do not vary for case:

Verbal morphology

The copule and existential verb show distinct forms for person and number:

In the rest of verbs present in the translations, there is too much inconsistency to believe in a regular paradigm. I will sketch them here:

- Present: no regular morphology in the 13 verbs in present. One case shows a signular/plusral distinction

- Infinitive: only one example: banaar (to judge), and there is a present form with the same ending: ribanar ('to write')

- In the past tense, some verbs end in vowel +ye. Nevertheless, this is also the most common ending for imperative (both negative and affirmative). Another more distinctive endiugn is -en.

- There is not a distinct morphology, being -e the most frequent form (3 out of 5 cases)

- For participle, most of the cases display -en or -e. This parallels the past-participle identity in some germanic languages

- For imperative, the most common ending is vowel + ye, with a lot of variation.

You can access my Formosan lexicon here.

Conclusion

There is not much that can be said about this conlang, other than Psalmanazar did a considerable effort by combining some verbal morphology from English and German, and a pronominal case system like English and Romance's. Nominal gender variation paralell's English's. Besides, some words get inspiration from Greek, like the preposition "apo", and the copulative conjonction "kay"('and').

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario